Here is the text of the talk I gave at Duke University Libraries on January 14. As usual, the questions & discussion were better than the talk. Also, please check out the partial list of sources for this talk.

As a Duke alum, I really wish I could ease into this talk with tales of roaming the stacks in Perkins way back when. But unfortunately, they would be just tales … and rather tall ones at that. I have to admit that I just didn’t spend much time in the library as an undergrad. I just wasn’t that kind of student.

I was here from 1983-1987, or as my classmates and I refer to it – the time of Johnny Dawkins, Jay Bilas, Mark Alarie, Tommy Ammaker and Danny Ferry. I spent way more time in Cameron and in Krzyzewskiville than in Perkins. I guess I’m just a late bloomer when it comes to my love of libraries.

The first Krzyzewskiville,

The first Krzyzewskiville,1986. From Kimberly Reed’s Krzyzewskiville Collection

I actually thought about using this talk as a way to share some ideas about how academic libraries could reach students like me … but I’m not sure I have any ideas that Duke isn’t already implementing. I love the Crazy Smart campaign, the Library Party, and the awesome study breaks you all host.

So I really don’t have anything to say to y’all about how to get students like me to use the library. I’m certain that if I got a second chance to be a Duke undergrad, I would hang out at the library all the time – heck, I want to hang out here all the time now. And just in case there is anyone here who was part of the library back in the 1980’s, trust me when I say it was me, not you.

So I know the topic is “Research Libraries and different clientele”, but I hope you will indulge me as I take this topic in a perhaps unexpected direction. In some ways it would be easy to use the topic to talk about how we ought to design our services and collections to serve the different needs of undergraduates, graduate students, faculty — even alumni and donors and the general public.

Another obvious direction for this talk, especially given my interest in diversity and social justice, would be to talk about different clientele in terms of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender and other forms of social difference. After all, librarianship remains nearly 90% white and over 80% female; while the projected college student population for 2021 is expected to be 58% white, and 58% female , with 17% of students being African American, 17% Hispanic, & 7% Asian/Pacific Islander.

So it might be easy to talk about how librarianship needs to address it’s own lack of diversity if we want to have any hope of reflecting and serving an increasingly diverse clientele.

But I decided to take the topic in a perhaps unexpected & decidedly more theoretical direction, because I think the future of research libraries depends on librarians making conscious choices about what a library is and who and what we serve.

So let’s talk first a bit about the whole notion that libraries, and universities, have clients – a concept I am frankly not very comfortable with and would like to challenge a bit.

It is true that our students, and their parents, are in fact increasingly approaching college with the expectation of gaining the marketable skills and credentials they need to compete in the job market. Faculty mostly see us as their buying agent – they want us to provide access to the research materials they need for their research and they then want us to buy their books and the journals they publish in. The university administration wants us to run ourselves more efficiently (“like a business”), and in some cases want us to find ways to turn some of our services into cost-recovery or profit centers.

The current reality for many research libraries certainly lends itself to thinking of our users and stakeholders as clients or even customers. We have the goods and services they need, and the whole system works best when we find the most efficient way to deliver those goods & services. And, of course, since everyone knows that academia is hopelessly inefficient; we must look to the business world for models of how to best serve our customers and to the “start-up” culture of silicon valley to learn how to innovate.

Shenanigans, by flickr user binkmeisterrick

Shenanigans, by flickr user binkmeisterrickWell, if you have read any of my previous writings, you know how I feel about that. I call shenanigans on that approach to libraries and the future of libraries. It is a philosophy that is (sometimes consciously, sometimes unwittingly) steeped in neoliberalism, and it embodies a definition of libraries that is at odds with my understanding of the core values of our profession – values like Democracy, Diversity, the Public Good, and Social Responsibility.

So what I really want to talk about is my belief that Neoliberalism is toxic for higher education, but research libraries can & should be sites of resistance.

To do that, it would probably be good to define neoliberalism. What is neoliberalism?

There are plenty of definitions – but I like this one from Daniel Saunders, who defines neoliberalism as “a varied collection of ideas, practices, policies and discursive representations … united by three broad beliefs: the benevolence of the free market, minimal state intervention and regulation of the economy, and the individual as a rational economic actor.”

Neoliberal thinking emphasizes individual competition, and places primary value on “employability” and therefore on an individual’s accumulation of human capital and marketable skills.

A key feature of neoliberalism is the extension of market logic into previously non-economic realms – in particular into key social, political and cultural institutions.

We can see this when political candidates promote their experience running a successful business as a reason to vote for them, and in the way market language and metaphors have seeped into so many social and cultural realms.

For example, Neoliberalism is what leads us to talk about things like “the knowledge economy”, where we start to think of knowledge not as a process but as a kind of capital that an individual can acquire so that she then can sell that value to the market.

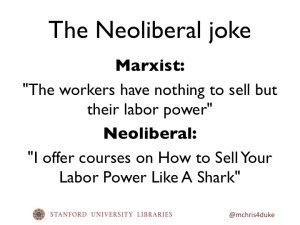

This is where I pause to ask if you have heard the joke about the Marxist and the Neoliberal? The Marxist laments that all a worker has to sell is his labor power. The Neoliberal offers courses on marketing your labor power.

The joke about the Marxist & the Neoliberal

The joke about the Marxist & the NeoliberalSo OK, Neoliberalism is a thing, a pervasive thing, and it includes the extension of market language, metaphors, and logic into non-economic realms – of special concern to us is the extension of neoliberal market frameworks into higher education and into libraries.

And it is really important to remember that one of the really insidious things about ideologies as pervasive as neoliberalism is that we barely notice them – they become taken for granted the way a fish doesn’t know it is in water, or the way many of us Dukies assume an obsession with college basketball is normal.

Obviously, I think this is a bad thing – not the obsession w/ college basketball, of course — but the neoliberal encroachment on education.

I am one of those hopeless idealists who still believes that education is – or should be – a social and public good rather than a private one, and that the goal of higher education should be to promote a healthy democracy and an informed citizenry. And I believe libraries play a critical role in contributing to that public good of an informed citizenry.

So the fact that the neoliberal turn in education over the last several decades has led to a de-emphasis on education as a public good and an emphasis on education as a private good, to be acquired by individuals to further their own goals is of particular concern to me.

In the neoliberal university, students are individual customers, looking to acquire marketable skills. Universities (and teachers and libraries) are evaluated on clearly defined outcomes, and on how efficiently they achieve those outcomes. Sound familiar?

We can find evidence of this neoliberal approach in plenty of recent trends in higher education – which are almost shocking in how blatantly they rely on a market model of education. The penetration of neoliberal thinking in higher education is so pervasive that it is no longer just market metaphors – colleges recruit students with blatant appeals to their economic self-interest and the mainstream argument for a strong education system is that it is an economic imperative – that we, as a nation, must invest in education in order to compete as a nation in the global economy.

As an example – This very recent article on fastcompany.com – Does Ikea hold the secret to the future of college? – reads almost like a parody of an unabashed, uncritical, unselfconscious neoliberal approach to higher education.

In discussing his enthusiasm for bringing his special brand of for-profit eduction to Africa, one educational entrepreneur explains, “There are a lot of young people in Africa who could be Steve Jobs”. It is no mistake that the justification for bringing “higher education” to Africa rests on the image of one of the richest & whitest men in America — someone who also happens to be a college drop-out, by the way.

In the article, the founder of First Atlantic University freely admits that he started this for-profit, blended learning institution in Africa as a solution to the hiring problems that his microelectronics firm is having. The real problem here is not that this dude has created a for-profit job training program that provides not only direct financial benefit to him but also provides a pipeline of future employees trained to meet his company’s labor needs … the problem is in calling that education instead of job training.

But it isn’t only the new for-profit universities that privilege corporate interests and the production of new workers.

All across the spectrum of higher education, including at institutions like ours, resources are shifting towards standardized market-driven curricula and programs and towards producing not the next generation of critically engaged citizens but rather the next generation of entrepreneurs.

Research libraries are, of course, not immune to the effects of neoliberal thinking and policies. I see it seeping into just about everything we do, and I hope we can talk about where you all see it (or not) and what we might do to resist it.

So, let me seed the conversation with a few of my own observations about the neoliberal influence on various areas of research libraries.

In terms of instruction & reference, neoliberal thinking tells us that information literacy provides students with a discrete set of skills (which we can easily measure and assess) that will help them on the job market.

Neoliberal thinking tells us a successful reference “transaction” provides the patron with the most efficient answer to their immediate information need. Neoliberal thinking mocks the idea that library instruction and reference might be about encouraging students to think critically not only about their own information consumption but also about the whole system of knowledge creation & access, and about who controls how we search and what we find. Neoliberalism scoffs at the idea that librarians ought to encourage browsing and serendipity and other forms of “inefficient” research and learning.

Neoliberalism frames this as a contrast between giving patrons what they want vs what giving them what we think they need. That formulation is a rhetorical strategy that makes librarians sound like condescending bunheads who aren’t hip to what the kids need.

What I want to suggest is that we can and should resist that rhetoric – both because it is incredibly sexist and ageist and because the tension is not between what our patrons ask for and what we want to give them; the tension is between a neoliberal, transaction model of library services and a model based on the mission of promoting critical thinking and equipping students to interrogate power and authority.

Neoliberalism has also really seeped into the way we think about collection development. We have become obsessed with measuring the value (defined almost always in terms of use only) of every item in our collection so that we can pare down our collection to its leanest, most efficient form. We are assigning actual dollar values to how much it costs to keep a book on a shelf, so that we can prove how much money our shared print storage programs save us … with no real consideration given to the non-monetary benefits of having large world-class print collections, on many topics and in many languages, in one location.

In many cases, we’ve also turned over collection development to the market by signing on to Patron Driven Acquisitions programs that essentially signal that we trust the free market to build our collections.

Neoliberalism has affected library staffing models as well. Whatever you think of faculty status for librarians (and my thoughts on that issue are constantly evolving), there is no denying that the erosion of faculty status and job security for librarians is tied to the same neoliberal emphasis on cost-cutting that is leading to the adjunct crisis across higher education.

Finally there is our obsession with assessment, and with justifying everything based on statistics and ROI or Return on Investment. I actually have a whole talk on why the ROI paradigm is a bad fit for libraries, so let me just say that it isn’t assessment per se that is a problem in libraries – it is the fact that we rarely measure things that actually matter (or should matter to us), and we rarely know how much of what we are measuring we are looking for.

But I guess the real question is Where should we go from here?

Where now? Photo credit Katie Young & Liz Gaudet

Where now? Photo credit Katie Young & Liz GaudetI’m not entirely sure, but like any good entrepreneur, I have a 3 step plan to get us started.

The first step is awareness. I urge librarians to critically examine the philosophical underpinnings of our own policies and programs. Read the works of critical scholars who call attention to the “scourge of neoliberalism” affecting higher education and ask yourselves where is that manifest in my own work?

Where is it manifest in the work of the thought leaders of librarianship – those who offer roadmaps for the future of academic libraries that involve thinking like start-ups and ceding responsibilities for general collections to the marketplace?

Step 2, if you agree that the values of librarianship compel us to resist the corporatization of libraries, is to find allies – amongst our own profession and across the academy. This is both harder and easier than one might think. Quite frankly, precious few of the dominant voices in academic librarianship speak from a progressive, critical, radical stance. I suppose in some ways that is to be expected – voices of resistances rarely emanate from the center. But once you decide to actively seek those voices, it doesn’t take any exceptional library sleuthing skills to find them. You can quite literally google “progressive librarian” and you can find both a journal and a tumblr by that name. “Radical librarians” turns up some great stuff too. And I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Library Juice Press, which is publishing top-quality work by and for librarians who want to engage in a more critical analysis of our profession and our institution, and who want to engage in a radical praxis of librarianship based on commitment to democracy, social justice, diversity and social responsibility.

Step 3: Do something. Collect archives simply because inclusion and social justice demands that works and archives of marginalized peoples are just as important (perhaps more so) as those of prominent, mainstream men and organizations. Sneak a little critical thinking into your information literacy sessions or reference encounters. Try something wildly inefficient and with no clear economic benefit.

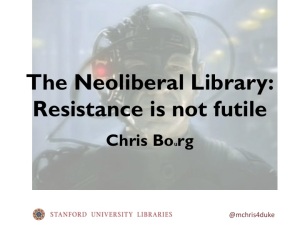

In other words Resist – It is not futile!

Jean-Luc Picard as Locutus after Borg assimilation, from Wikipedia article on Borg (Star Trek)

Jean-Luc Picard as Locutus after Borg assimilation, from Wikipedia article on Borg (Star Trek)So to try to tie this all back to the original topic – Research Libraries and different clientele – I guess my whole point is really that we ought to

reconceive of our clients as not simply the undergraduates, graduate students, or faculty around us. Let’s start thinking about social justice as our client, or democracy, or an informed citizenry; and then let’s consider how our priorities and way of working might change as a result of that kind of thinking.