Below is the slightly edited version of the closing keynote talk I gave at ACRL OR/WA 2014.

Great conference, really cool people, gorgeous setting.

_________

The theme for ACRLORWA14 is Professional identity and technology: Looking forward, so I figured I would start with a little about my own identity.

When I think about professional identity, the sociologist in me kicks in and I think of identity as part and parcel of our social location and as very much tied up in the kinds of characteristics that are so central to social interaction in our culture: gender, race, social class, sexuality.

Title slide, closing keynote ACRL OR/WA 2014. Librarianing to Transgress

So to situate myself in terms of my identity and how that affects my perspectives — personally professionally and politically– I am a queer white woman from a working class background with a Latina wife. I am a feminist who’s politics are liberal, bordering on radical. And of particular relevance to my thoughts on the role of academic libraries and librarians, I believe in the possibility of education as the practice of freedom as articulated by bell hooks in her 1994 classic,

Teaching to Transgress; which is the source of both the image here and the title of my talk.

You might also notice that I like to use the word librarian as a verb, so the 6 word story library identity version of Who I am is:

Queer butch feminist, librarianing for justice

When I was first asked to give this talk, I was told that folks might be interested in me expanding on some online comments I had made at the time about the responsibilities of large research libraries (like Stanford, I suppose) to lead technological change that is attainable for all institutions. Since many of the folks here are from smaller libraries, it makes sense that you would be interested in a talk that articulates a shared technological future that would be realistic and sustainable across types and sizes of libraries.

But that isn’t what I’m going to talk about.

I’m going to talk about something different, because between the time I was asked to give this talk and now, several things have happened that have convinced me that the need for a future based on shared technology is far less urgent than the need for a future based on empathy and shared humanity.

By shared humanity, I simply mean a sense of and commitment to the idea that all lives matter, that all people are deserving of justice, equity, & dignity, and that all voices need to be heard in the conversations that shape our future.

I want to use this opportunity to talk about the bigger issues and themes around shared humanity, equity, & social justice that I think should be motivating the work of librarians now more than ever; and I’ll try to include some ideas and examples of ways technology can be leveraged to help us create and share resources and facilitate conversations and connections in our communities in ways that might move us all closer to a sense of shared humanity. As a bonus, I’ll even try to relate what I say to the conference theme of professional identity.

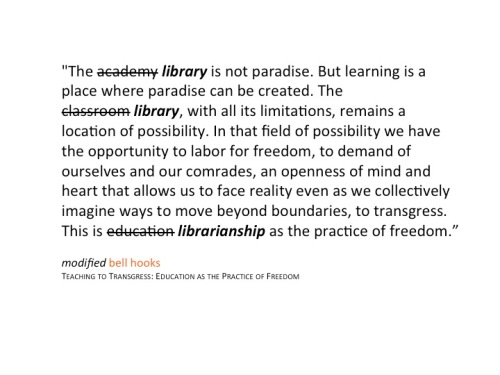

Let me go back to the bell hooks allusion from the title of my talk and give you one of my favorite quotes from Teaching to Transgress:

“To engage in dialogue is one of the simplest ways we can begin as teachers, scholars and critical thinkers to cross boundaries, the barriers that may or may not be erected by race, gender, class, professional standing, and a host of other differences.”

bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom

That notion of dialogue as education and the idea that authentic, messy, hard, critical conversations can break down barriers and create spaces for empathy and opportunities for us to experience our shared humanity is what has motivated most of my career in higher education and in libraries, and it is certainly what is motivating my talk this morning.

The key message I want to share in this talk is that librarians – in part because our identities are tied up in a specific set of professional values – are especially well suited to provide the spaces — physical, virtual, and metaphorical spaces — where our communities and our students are equipped, inspired, and supported in having difficult dialogues about hard social issues.

So, as I said, a number of things have happened between the time I agreed to give this talk and now that make it nearly impossible for me to imagine giving any kind of talk that doesn’t foreground issues of social justice and equity.

Let me be explicit about some of the events I am talking about.

#Ferguson happened.

On August 9, Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, was shot & killed by a police officer in Ferguson MO. In the weeks, now months, since Michael Brown’s death, the residents of Ferguson, and others, have engaged in nearly non-stop vigils, protests, and rallies to call attention to police brutality and to racist policing. The excessively militarized response by police to the mostly black crowds gathered in Ferguson, especially when compared to the far less harsh responses to the mostly white college students who rioted and set fire to vehicles during a pumpkin festival in West Virginia last weekend, have fueled a sense of – a recognition of – the deep & persistent racial divide in this country.

Another key event, closer to home – at least professionally – is the $1.25 lawsuit brought against 2 female librarians for speaking out about sexual harassment and for identifying by name a man who’s repeated creepy behavior towards women at library conferences is so well known that women routinely warn one another not to be alone with him. The lawsuit, and the online discussions, most of which are happening under the twitter hashtag #TeamHarpy, have spurred conversations ranging from sexual harassment, to codes of conduct at library conferences, to the problems with “rock-star librarians”.

Another controversy that has raged on social media this summer is #GamerGate – which has more recently moved from blogs and twitter to mainstream newspapers like the New York Times and The Washington Post. Gamergate refers to a controversy in the gaming industry that theoretically started out as calls for ethical standards in game reviews but that soon warped into some of the sickest sexism and misogyny on the internet, including death & rape threats credible enough that several prominent women in the gaming industry have been essentially forced into hiding to protect themselves and their families when their home addresses were revealed online.

These recent events have me thinking even more than I usually do about issues of race and gender and power, and other forms of oppression and inequality. In terms of this conference and its theme, I am convinced that when librarians think about identity and communities, we need to pay special attention to gender, race, class, sexuality, and other intersecting axes of difference and inequality – and we need to be prepared to equip our students to understand these issues and to navigate difficult conversations about inequality, sexism and gender bias, institutional racism, and privilege.

Which brings me to the other big event of the summer — the firing of Steven Salaita in August from a tenured faculty position at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

For those not familiar with the #Salaita story, Professor Steven Salaita was offered a tenured faculty position at UIUC, only to be terminated from that position (before he even began) because of the “uncivil” nature of tweets he posted regarding the actions of the Israeli government in Gaza. Salaita’s termination has been met with harsh criticism by those, like me, who believe his firing for “uncivil tweeting” violates the principles and values of free speech and intellectual freedom.

Many scholars have joined boycotts of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, refusing to speak there or otherwise engage with the university until Salaita is reinstated, and many of the departments within the University itself have gone public with votes of “no confidence” in the administration and board of trustees. (Note: Those so inclined can add their name to the list of LIS scholars and practitioners who support Salaita. Kudos to Sarah T. Roberts for her work on this.)

On the other hand, a number of university administrators (e.g. University of California at Berkeley) have used the Salaita situation as an excuse to issue campus-wide calls for “civility”, arguing that free speech must always be balanced with an obligation and expectation of courteousness and respect. As you might expect, critics of these top-down “civility codes” note that calls for some subjective measure of courtesy could easily be used to censor academic freedom and stifle debate on some of the very issues that are most pressing and simultaneously most controversial in our society.

So, in the wake of #Ferguson, and #TeamHarpy and #GamerGate, and the Salaita firing; I found myself incapable of writing a talk about shared technology when all I can think about is the need for librarians to leverage our skills and our knowledge and our values and our identities and yes, our technologies to help our students and our communities develop a sense of shared humanity and empathy, in the fragile hope that we might make some progress.

Why librarians? And how would we do it?

For me the answer to “why librarians?” is because of our values – we are one of the few professions that boldly proclaims diversity, democracy, social responsibility, intellectual freedom and privacy as core values.

(As an aside, I always feel like I need to remind us that our values state that we “strive to reflect our nation’s diversity”, but that at 88% white we either aren’t striving very hard, or maybe we kinda suck at it….but that’s a whole other talk).

I very much believe that libraries ought to be the places on campus where community members, students especially, feel the most free to talk about difficult topics, to express the full range of opinions and yes emotions, on the highly charged topics that are part of their social world. College is a time when young adults are forming and reforming their identities, and they need spaces where it is safe to try on opinions and ideas and feelings about the world and their place in it.

I love the fact that libraries are often that place and I think libraries should be that place.

One advantage many of us have as librarians on a college campus is that we are adults with lots of information and expertise and knowledge to share with students, but we mostly don’t have much authority over them, especially in the sense of grading them. That produces a kind of setting, and the possibility of a kind of relationship where students can be intellectually and emotionally vulnerable in front of us and with us. That is a big part of what I mean when I say we are especially well suited for creating spaces for the kinds of dialogues that bell hooks tells us will help us all cross boundaries and establish some sense of shared humanity.

But for me, it isn’t just about creating those spaces & opportunities for transformative learning experiences, but it is also about providing access to the information and the tools to understand current events and to evaluate the many increasingly polarized views on events like #Ferguson or #GamerGate or the conflict in Gaza.

So let me get to the how by sharing some examples of ways librarians and others have leveraged technology to pull together and share information on current events, thus creating not just the space for dialogue but also the context for learning through dialogue:

My first example comes from the Stanford University Libraries – in December of 2012, right after the Sandy Hook school shooting, our geospatial center staff began collecting data on mass shootings in America. They compiled quantitative and descriptive data about mass shooting incidents since 1966, and produced maps and charts and a dataset intended to aid in our collective understanding of mass shootings in America. All of their work, the dataset, the maps, and the charts are available under a creative commons license for all to use. To me, this is a great example of librarians & libraries creating resources to help our patrons make sense of a complicated, tragic and emotional topic.

Ukraine exhibit, Green Library, Stanford University

A less technical example also from the Stanford University Libraries is our commitment to current events displays – like our recent info display about Ukraine. Our

Slavic and East European subject specialist put together a set of resources to provide some context to students about Ukraine – these resources included a map of the territorial evolution of Ukraine, the languages of Ukraine, basic demographic and economic data about Ukraine, and a selection of books for students who wanted to explore the topic in more detail. We have addressed other recent current events via blog posts, twitter, and book displays.

In response to events in Ferguson, librarians and archivists at Washington University in St Louis are building a community sourced digital archive of “photos, videos, stories and other content related to protests, unrest in Ferguson”. They are using existing technologies – Omeka and ArchiveIt – to collect and provide access to relevant content; and social media to raise awareness of their work and to solicit contributions to the archive.

It is interesting to me that as far as I know, they are doing this with existing staff and resources. The Sloan Foundation funded two earlier crowdsourced digital archives, the September 11 Digital Archive and the Hurricane (Katrina) Digital Memory Bank.

There is a great piece by Courtney Rivard, about the different responses to the September 11 archive and the Katrina archive in terms of quantity and type of items deposited. Basically, much more content was deposited in the September 11 archive, and much more content from a more distant perspective. In both the materials collected and in the media September 11 was seen as a national event, and victims were quickly anointed as national heroes; while Hurricane Katrina was seen as a more local event, with victims labeled with far less charitable and not so subtly racist, terms.

It will be very interesting to see how response to the Ferguson archive compares, and whether materials deposited will be primarily local and first hand photos, videos and stories; or whether it will generate a broader national response and therefore a larger and more diverse archive. Even crowdsourced archives are not created in some neutral race-blind vacuum; and today’s social biases impact future scholars and the kinds of archives they will have access to.

Data collection isn’t neutral either.

The FBI collects a whole bunch of data on crime – arrest and crime incident reports from every local police force are consolidated at the national level and arrest data is available by age, race & sex of the arrestee for 28 different categories of offenses – including, of course, shooting a police officer. But there is no national database to tell us how many people are shot by police officers, nothing to tell us the age, race, and sex breakdown of who gets shot by police officers; nor anything else about the circumstances.

There are a several interesting civilian attempts to put together data on police shootings. For example, the blog Deadspin has a project where they are asking volunteers to help them populate a google docs spreadsheet by conducting google searches for police shootings for every day from 2011 to 2013.

D. Brian Burghart, a journalist and journalism instructor at University of Reno, Nevada is using Freedom of Information Act requests and crowdsourcing to create a database of all deaths through police interaction in the United States since Jan. 1, 2000. His website fatalencounters.org has maps, spreadsheets, crowd visualizations and lots of info about how he is collecting and verifying the data.

For me the obvious question is could/should librarians be developing these kinds of resources? I think so.

One final example of the kind of crowd-sourced resources that developed in the aftermath of Ferguson was a set of teaching materials and resources, mostly under the hashtag #FergusonSyllabus. There are actually many such resources, but not surprisingly my favorite was developed by group calling themselves Sociologists for Justice. Their syllabus provides a list of “articles and books that will help interested readers understand the social and historical context surrounding the events in Ferguson, Missouri, and allow readers to see how these events fit within larger patterns of racial profiling, systemic racism, and police brutality.”

I wonder how many faculty on our campuses might have been looking for just such a set of resources as they struggled with how to facilitate productive conversations in their classrooms in the aftermath of Ferguson?

I know of a few librarians who created resource guides about Ferguson – Washington University at St. Louis has one, and the law library at SUNY Buffalo has one. There may well be others that I don’t know of, but what I didn’t see was librarians coming together to crowdsource some great research guides for our communities the way other educators came together quickly to create #FergusonSyllabus.

That would be the kind of collective action I mean when I say I am calling on librarians to use simple, existing technologies to produce, uncover, promote, and inspire deep dives into highly charged topics.

OK – I’m going to wrap it up soon, but some concluding thoughts first.

We are librarianing in messy, polarized and yes, still sexist, racist, homophobic times.

Despite tremendous progress up through the 1990s, the gender revolution has stalled – white women still make .78 to every dollar a man makes, and black and brown women make even less than that. #GamerGate, #TeamHarpy and far too many other examples – including a Pew report released yesterday – remind us that women are harassed and threatened and assaulted, online and off, at horrifying rates. And Michael Brown’s death, the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the killing of Trayvon Martin, and too many similar stories remind us that we are not living in the race-blind world many thought would come after the great civil rights victories of the 60s and 70s. Racism is real, and there are troubling and persistent racial disparities in wealth, income, education, health, and homelessness; as well as often wide racial differences in perceptions and opinions about important events. For example, 71% of African American residents of Ferguson believe Darren Wilson should be arrested and charged w/ a crime for killing Michael Brown. The same percentage of white residents think Wilson should NOT be arrested and charged.

These kinds of polarizing views and perspectives can make it very hard to talk about race. In fact, one alternate title for this talk was going to be “What’s a nice white girl like me have to say about race & librarianship in the wake of Ferguson?”

But/and we as a society have to talk about race and gender and other highly charged topics if we are going to have any hope for progress. And to my mind, the college students we work with just might be the best hope we have for making progress on issues not just of equity and social justice, but on a host of other big challenges we face – things like climate change, energy, global health, and poverty.

I think our focus as librarians ought to be on how to best equip our communities, especially our students, to understand and make progress on addressing these challenges.

I think one of the most effective and the most uniquely librarian-y ways we can do that is by creating spaces (real and virtual) where the free exchange of ideas and thoughts and feelings, with all of the accompanying “uncivil” messiness and anger and passion, is accepted and encouraged. I think we can and should work together, using sharing technologies, to fill those spaces with data and history and context to inform and enrich those conversations. It is through dialogue in safe spaces that barriers are broken down and empathy begins to develop.

Ultimately, I believe that unless and until we as a society develop a greater sense of our shared humanity and greater empathy for the many different kinds of people we share this planet with; the technologies we create and use, regardless of our best intentions, will reflect and then perpetuate the same racist, classist, sexist inequities that continue to persist in society.

Bottom line: worry about humanity first, technology later; and keep on librarianing.

______

There are many more examples than the ones I mentioned of librarians and others doing exactly the kind of work I am calling for, and I very much hope folks will share those examples in the comments or elsewhere. One excellent example that I am embarrassed to have left out is the weekly #critlib twitter chats. To learn more, check out the #critlib Chats Cheat Sheet.

![Portrait of baby sitting in chair Born, Julius. [Portrait of Baby Sitting in Chair], University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting River Valley Pioneer Museum, Canadian, Texas.](https://chrisbourg.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/med_res.jpeg?w=215&h=300)