Modified Text of talk I gave at Ivy Plus Discovery Day at MIT.

(Note that I tidied up this text while watching the DNC last night, so blame Pat Spearman, the Collins brothers, and Michelle Obama for any errors.)

I love that this gathering is Discovery Day, not search day, and not find day. Because, to paraphrase that sort of famous Roy Tennant quote from way back in 2001 “Only librarians like to search, everyone else likes to find … and lots of folks like to discover”.

And that’s where the title for this talk comes from, so thanks Roy!

Lots of folks like especially to discover things they didn’t know they were searching for and didn’t know they wanted to find.

I know it isn’t cool for librarians to talk about serendipity anymore; but I think it might be time for librarians to make serendipity cool again. More importantly, I think it is time for librarians to take serendipity seriously.

I want us to take serendipity seriously for at least 3 reasons:

- Because some scholars really think it is important to their work

- Because facilitating real serendipity through and in our discovery environments, is one way we could actually contributing to more equitable and open access to information and to learning and research

- Because serendipity is fun

Some other time, I’ll unpack and explain what I mean about # 2 there – the equitable open access part of discovery. For this talk, I want to concentrate on the that discovery and serendipity are important and fun.

I’m going to assume you know what fun is, and what important means, and what discovery is; but let’s define serendipity, or better yet, let’s just let the OED do so (I would link, but paywall):

From Oxford English Dictionary: Serendipity = The faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident. Also, the fact or an instance of such a discovery.

And of course, you can’t talk about serendipity without talking about browsing. Over and over, we hear faculty –usually but not always, humanities faculty — talk about the importance of browsing precisely because of the sense that browsing facilitates serendipity. Often these defenses of browsing and serendipity seem to be part and parcel of a concern over the loss of space for physical collections and the lamentable fact that on every college and university campus I know of, a higher percentage of physical library collections are in off-campus, non-browsable storage every year.

But I find that when we really listen to faculty talk about the value of serendipity and browsing to their work, it really is not just nostalgic luddite longing for a mythically comprehensive physical library of yore.

What I’m increasingly hearing, especially here at MIT and in the context of the conversations we have had as part of our Task Force on the Future of Libraries, is an excitement about and a yearning for a new kind of online discovery environment that does more than replicate physical browsing but actually capitalizes on the promises and affordances of technology to facilitate even greater serendipity and to make browsing even more productive and even more fun.

[Interesting side-note: the faculty I’m hearing from at MIT don’t actually use the terms browsing or serendipity. They talk instead very explicitly about wanting tools that will point them to things they don’t know that they don’t know.]

What we are hearing are scholars who want us to build tools, or facilitate the building or deployment of tools, that will allow them to see connections to their work and their teaching and their interests that they cannot see now. They want to discover articles and books and data and images and maps and primary sources and teaching objects and people on the fringes of their own areas of focus, but that are otherwise kind of in their blindspots. They want to make happy & unexpected discoveries; and they want it not to be by accident, but to be because the library has provided the tools, the data, and the metadata to make it so. [One of the many things I love about MIT is how many faculty and students really do seem to get the important role the libraries play in creating and maintaining metadata and infrastructures to provide discovery and access to content.]

And it is important to note, that these are faculty and researchers at MIT we are hearing from; and they are mostly NOT humanists – they are primarily engineers and scientists.

I don’t know about you, but the idea of developing and/or deploying and supporting discovery environments and tools that create and inspire entirely new kinds of serendipity and browsing sounds pretty exciting and fun.

And, it sometimes feels like it is way past time to do it.

When I talked about this to a group of women alumni from MIT, one woman in the audience was quick to tell me about work done 20 years ago at MIT on this very topic. (Yes, that was a bit of serendipity for me, brought about not by technology but by in person interaction.)

In 1994, the famed designer and scholar of design Muriel Cooper, who founded the MIT Media Lab’s Visual Language Workshop, gave a presentation at something called TED5 – which may have been the precursor to what we now know as TED talks, I haven’t verified that yet – but anyway at this talk in 1994, Muriel Cooper wowed the audience with her concept of “information landscapes”.

And here I’ll quote from a 2007 text titled “This stands as a sketch for the future: MURIEL COOPER and the VISIBLE LANGUAGE WORKSHOP”.

In that text, David Reinfurt describes Cooper’s information landscapes as

immersive three-dimensional environments populated not by buildings but by information… In an information landscape, the user appears to fly effortlessly through the infinite zoom of a textual space, reading along the way, creating connections and making meaning.

Unfortunately, there is no video of the 1994 talk, but after Cooper’s death some of her students made a video about the Information Landscapes concept, and I want to show you a bit of it.

(I only showed a few minutes of the video at the talk – I started it at about the 5:00 mark. You should watch the whole thing, and definitely stick around to the very end for a delightful bit of Muriel herself).

I love the contrast between the dated feel and sound of the voiceover and the truly prescient ideas about a 3-D information space full of advanced, user-controlled data visualizations and multiple ways to link and organize concepts. Muriel Cooper sadly passed away less than a year after presenting these ideas at TED5 in Monterey; and while her students and others have continued to do amazing work on immersive technology and data visualizations, Muriel’s vision of an information landscape hasn’t really penetrated the way we search for, find, and discover information and knowledge.

I have to say it is a little sad to me that 2 decades later, our best library search environments look like this:

The rest of the search world, even best in class like Google and Amazon, aren’t really that different:

The library search community went through its phase of trying to be more like Google and Amazon – for good reasons, our patrons wondered impatiently why we weren’t more like them– and now I’d say we are mostly pretty close. At least in all the basic structural and conceptual ways:

- one search box to rule them all

- results displayed in a linear list that is ranked on some meaningful dimension

- the goal is to find items, 1 at a time; not concepts, not relationships

Why is that? Why are we still searching in 2-D, linear interfaces for items rather than for concepts?

I think a big part of the reason is because it works well enough. And in fact, it works really well for finding stuff we know we want.

And here is where it is really important to point out that what the Task Force on the Future of Libraries heard from library staff about discovery was very different from what faculty and students told us. The MIT Libraries staff made it abundantly clear that the most common struggle our patrons have is with finding a known item – that is the most common kind of question we get and I’m pretty sure it is what our data tell us is the most common kind of search in our catalog.

So how do we reconcile this seeming contradiction?

People want to find what they want and they expect library search tools to be just as good as Google at helping them do that.

But/and, when asked to describe an ideal discovery environment of the future, scholars – at least the MIT folks we have heard from (and folks I talked to while I was at Stanford) – imagine something much more exploratory, more relational, more immersive, more inspiring, and more playful than what any of us have right now. It is as if they trust that the tools that allow them to find what they know they want are good enough and will always be good enough; so when they think of a future they want something they can’t do now (to be fair, that is what we asked them to think about).

To be clear, I don’t think they want this hypothetical immersive and playful and serendipitious environment to completely replace the utilitarian search tools they have at their disposal right now. They are happy to keep using the combination of tools they use now when they need to find what they need to find.

But that means that we in libraries have I think felt kind of compelled to keep trying to give them what they want right now, while not really having the resources to try to develop the kind of information landscapes Muriel Cooper imagined more than 20 years ago.

It is a difficult dilemma, with no easy answers. And it is even more complicated by the fact that the corpus of stuff we in academic libraries are trying to help people discover and access is part of a scholarly communication landscape that is far more complicated than it needs to be and that is, in large, shaped the way it is because so much of it is controlled and disseminated by commercial players whose interest aren’t always aligned with the mission-driven interests of academia (I digress — that’s actually a whole other talk I should give sometime).

And to highlight something we all know — we in academia and in libraries don’t have unlimited resources. So I think we need to be smart about partnering with those commercial players whose visions do align with ours and whose resources and partnerships can help us move closer to a new kind of discovery without having to abandon what works well enough right now.

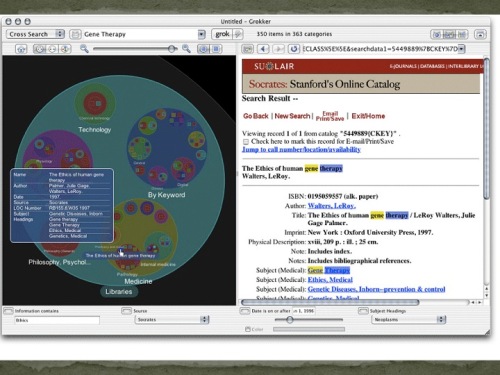

Back in the early 2000s, I was involved in a project at Stanford Libraries, where we partnered with a start-up called Groxis on developing a visual search tool called Grokker.

It was a really fun project and a promising tool that generated a fair amount of buzz in the library world and in the search world. Grokker basically organized your search results into circles or bubbles by concept; so if you searched for “jaguar”, for example, you would get a bubble with items about the luxury car; another bubble with items related to the animal; and another with stuff related to the English heavy metal band Jaguar – which is a great example of how tools like this can help you discover things you didn’t know you didn’t know. I had never heard of the heavy metal band Jaguar until I got involved with the Grokker project.

Unfortunately, this is the best image for Grokker I can find – from a 2004 Stanford Libraries newsletter. And I can’t demo it; because the company and the product pretty much disappeared after a hostile take over of the board by members who apparently wanted the company to abandon the education market in favor of a seemingly more lucrative corporate focus. That didn’t work out so well for them, and searching for any evidence of Grokker or Groxis now leads to a few articles and blog posts (mostly by librarians) and lots of dead links.

But – working on Grokker and testing it with faculty and students at Stanford gave us/me a sense of the possibilities of new ways to search. There were, of course, the usual concerns with new things like this – if the content included isn’t “comprehensive” in a way that matches the user’s expectations, then they tend to think it doesn’t work.

BUT – lo these many years later, I still remember that nearly every person I talked to who tried Grokker described it as fun and spent considerable time playing with it.

Fast forward over a decade later, and we at MIT Libraries are poised to give our community the chance to play with something that looks a bit like Grokker but is actually even more intriguing – and that’s Yewno.

Yewno’s ‘search’ is powered by machine learning, computational linguistics, and semantic analysis; and its interface combines data visualization and concepts from neural networks to create a discovery experience that is closer than most to the way the human mind actually works. It doesn’t quite achieve the fully immersion landscape feel of Muriel Cooper’s vision, but it goes beyond what Grokker did to provide a more interactive visual journey through information about a concept. At the risk of sounding like a Yewno commercial, I’ll quote from their promotional material:

Unlike traditional search, which strives to provide the singular correct answer as quickly as possible, Yewno enables the connection of multiple concepts and information.

This is a tool that aims not to be better at search, or to help people find what they are looking for more efficiently. This is an environment that aims to help people discover and to learn about what they don’t know they want to learn.

I think we will learn a lot about discovery and about new ways of navigating information from Yewno. My secret hope is that some really brilliant MIT student or faculty member will play with Yewno, be captivated by the idea, decide that the interface is lame, and build something based on the same idea but better.

My dream discovery environment is one that provides the experience of browsing and interacting with books and articles in print and online simultaneously – I don’t know what it looks like exactly, but I imagine a virtual or augmented reality environment that simulates the best tactile (and emotional) experiences of browsing in a physical library with the vast resources and accessibility of digital resources and the efficiency of online browsing. Imagine if you really could browse the collections of all the great libraries at once – their physical books, their electronic resources, even the books that are currently checked out – from wherever you are; and your mind and body would feel like you were “in a library”.

And my dream discovery environment is playful and fun. Discovering something you didn’t know you wanted is fun. Finding what we are looking for is certainly satisfying (and not finding it is frustrating), but realizing some new connection you hadn’t thought to eplore, stumbling on some piece of information that adds a new dimension to your research or takes you down an unplanned but totally productive path – those kinds of discoveries are fun. There is joy in that kind of learning while researching.

I guess the big take away for me is that what I have heard from our community compels me to try to shift my focus from satisfying immediate user needs by continually improving the tools at hand to making progress and supporting progress towards a discovery environment we can’t yet imagine (because most of us are not Muriel Cooper) but which provides fun, intuitive, maybe immersive opportunities for discovery.

Some closing provocations:

Let’s consider what we might do, even in and with our current tools, if we took seriously the faculty who say they want to make happy and unexpected discoveries in the library – even, especially, in a library that is primarily digital.

What if we decided that the set of current tools for searching and finding are just fine, and we freed ourselves up to work on discovery?

Are there ways we can do that by promoting and supporting and partnering with organizations and people who are trying to create entirely new information systems and landscapes?

Are there ways we can do it by promoting fun and serendipity in our own existing tools and environments?

What can we do to learn more about what works and to spur our own and our communities’ collective imaginations about what discovery could be?

Funny how the more practiced you are at searching, the luckier you seem to get…

Maybe we need to distinguish between unexpected discovery (“I deliberately scanned the results from the shelf browse function in the library search engine, and found other materials I would not have otherwise uncovered.”) and accidental discovery (“I clicked on ‘Random article’ in Wikipedia and an interesting article about my research came up!”) because to me there’s a difference between the skilled use of a well-designed system that uncovers desired results and someone “pulling a Homer” in just getting incredibly lucky by using a random search technique that most librarians wouldn’t condone.

I’m not a fan of touting accidental discovery, but I don’t disagree with anything written here.

View at Medium.com

LikeLike

Thanks, Chris, for riffing off my line and going to a really great place with it. I like the idea of trying to put serendipity back into the discovery process and I hadn’t been aware of Muriel’s work, so thanks for that. To answer your question — yes, the TED5 Conference that Muriel spoke at was indeed the early days of what became the TED empire. See here for verification: https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization/history-of-ted

LikeLike

I also meant to say that linked data will likely provide a scaffolding for these new kinds of discovery environments. The links that are made explicitly won’t be enough by themselves, but they can serve as an initial set of connections upon which we can (presumably and hopefully) build.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the kind and generous comments Roy! And for doing the reference work on TED5 for us.

Someone smarter than me made a very similar point about linked data during the Q&A – I’m definitely sold on the potential.

LikeLike

I appreciate this post very much. From as long as I’ve been researching and transitioning into digital access, I’ve been concerned and disappointed with the lack of sense of embodiment in discovery. Taking the students through an aisle or two of the stacks related to the subjects they’re studying and letting them “find their way” and hopefully “feel” themselves “feeling” for certain spines, terms, avoiding stools, turning corners… to “situate” and “activate” their bodies…and then interpret web search tools and databases according to the many directives in place that limit their senses by “using” their senses, and direct their paths for them instead of opening an umwelt of potential…these sorts of projects are necessary attempts I believe at keeping research, brains and thinking – creatively embodied. And will help us to know whether a binary digital code will ever be capable of it (if that’s what we wish it would be)… or whether on/off electron activity in sequences has a limited human tool-use, and all the shades between 1 and 2 (or 1 and 1) and on or off, are tremendously significant aspects of world for us (and perhaps itself – though there we begin conjecture). Thank you for working and drawing attention to these things.

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughtful comments. Lots to think about and experiment with in augmented and virtual reality spaces.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have really appreciated the work of Andrew Hinton “Understanding Context” in this regard, as well as Peter Morville at Semantic Studios. So glad others are not content with the uni-directional emphasis of corporate searchware.

LikeLike

As yewno (see what I did there? ;-)) serendipity doesn’t just happen. It takes physical proximity but also metadata and most importantly actual control of content imho. In other words it takes libraries.

LikeLike

Dude- I said that:

“They want to make happy & unexpected discoveries; and they want it not to be by accident, but to be because the library has provided the tools, the data, and the metadata to make it so. [One of the many things I love about MIT is how many faculty and students really do seem to get the important role the libraries play in creating and maintaining metadata and infrastructures to provide discovery and access to content.]”

LikeLiked by 1 person

at least I didn’t leave a comment like “my cousin told me I would love this blog …” :-)

LikeLike

but you did send a link to your cousin, right?

(also, for everyone else – James is an old friend and colleague and I totally welcome all his comments, even if I sometimes like to bust his chops. only bec I miss him)

LikeLike